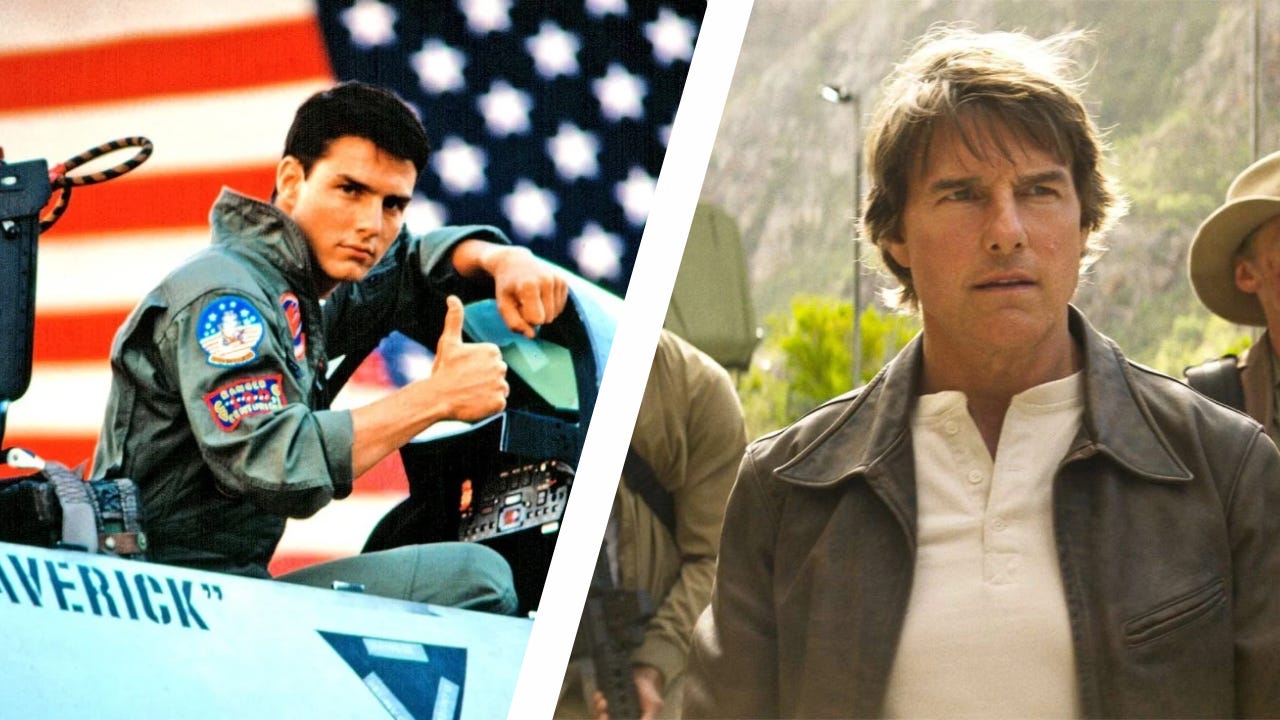

Ever since Tom Cruise unexpectedly saved the movie theater in 2022 with Top Gun: Maverick, he has become something more than an action flick movie star. Cruise has become an icon of the post-cynical vibe shift.

After Top Gun: Maverick roared back onto the big screen with high-octane sincerity and won over both critics and audiences exhausted by Hollywood’s decades-long obsession with deconstruction and ideological preachiness, Cruise announced two final installments in the Mission: Impossible series. These movies have been fun, but it’s more than just the death-defying stunts that have brought Cruise back to the heights of stardom that rival what he enjoyed in the 80s and early 90s.

It’s his relentless positivity, the way he earnestly celebrates other films, and his unapologetic try-hard demeanor, which feels like a recovery of something we’ve lost in our culture since the advent of our age of ironic detachment hit pop culture in the 90s.

Tom Cruise became an emblem of the vibe shift—an icon of what it means to be unapologetically aspirational in a post-cynical age.

Cruise never does the Ryan Reynolds’ wink-at-the-camera thing. He’s never detached. He’s relentlessly sincere.

But that kind of aspirational sincerity fell out of fashion for decades, and only now are we starting to sift through the rubble of all we deconstructed to recover the values we need to rebuild culture.

From Poster Boy of the Modern Story to Exile in the Anti-Story

In the 1980s and early 90s, Cruise was the golden boy of American modernism. His characters—whether in Top Gun, Days of Thunder, or A Few Good Men—embodied the modern story: self-made success, obvious moral categories, and the celebration of an upward trajectory in life. He was the personification of the American meritocratic dream.

But by the late 90s, the cultural winds had shifted. Postmodernism, suspicious of grand narratives and allergic to sincerity, dominated the zeitgeist. Earnestness was embarrassing; that was a signal you believed you were in the right story. To try too hard was to expose your naivety. It signaled that you just didn’t understand, that everything is just about power and who has it.

Aspirational action stars who set out to slay dragons and save princesses were out. Nihilism and ironic social commentary were in.

Cruise, for a while, looked like a man without a country. A strange detour through Scientology, a few erratic interviews, and some experimental roles to try and fit in with the moment (Vanilla Sky, Magnolia, Eyes Wide Shut) made him feel increasingly out of step with the culture. Even as he kept pumping out Mission: Impossible sequels, his broader persona seemed caught in a cultural no-man’s land. We weren’t sure what to make of a man who ran like it still mattered.

Sincerity, Stunts, and the Return of the Real

Then came the metamodern moment. A cultural shift that doesn’t throw irony out the window, but repositions it. In place of detached cynicism, there’s a longing for meaning, even when it’s risky or cringeworthy. Postmodernism asked, “Can you believe in anything?” Metamodernism replies, “We have to try.”

This is Cruise’s natural habitat. Few actors today commit as fully, not just physically, but sincerely. He doesn’t wink at the audience. He leaps off cliffs for them.

When CGI disembodiment is the norm, he’s doing something astonishingly analog: showing up by throwing his own body off cliffs on real motorcycles and dangling off the wings of biplanes.

That’s part of what’s created the revived attraction to Cruise as an iconic, metamodern movie star. His stunts aren’t just thrilling—they feel like acts of defiance against apathy, nihilism, and cutting corners.

And there are good reasons why that feels refreshing…

Rewiring the Brain for Meaning

Research in behavioral and cognitive science suggests that people experience higher existential satisfaction when they’re engaged in purposeful action toward long-term goals. Those goals are shaped by the story we believe is true, which we attempt to live into with our daily lives. Our loss of shared story in our culture in the postmodern age has created a vacuum of meaningful goals to pursue.

Even if it’s just through action films, Cruise models commitment to craft, willingness to risk toward goals, and the pursuit of excellence—traits our brains recognize as vital to well-being. When we witness someone who is all in, we’re invited to remember that meaning is something made through devotion and risk toward something good.

Psychologist Jonathan Haidt has noted that many young people today suffer not from a lack of pleasure, but from a lack of meaningful risk. Too much scrolling, too much self-monitoring, and too little purpose. Cruise, by contrast, isn’t detached. He’s intensely, almost absurdly attached to his work, to his mission, to the possibility that it might all matter.

From Detachment to Committed Participation

We’ve spent the last few decades learning how to deconstruct. But many are now realizing that you can’t build a life—or a culture—out of critique alone. Something in us wants to join again. To care. To act. To look up.

Cruise is, improbably, an icon of this return to try-hard sincerity.

I have no idea what his relationship to the cult of Scientology is like any more, and by no means do I intend to elevate him to being some cultural messiah. But to be people of renewal requires that we, as the Apostle Paul once wrote, “hold fast to what is good.”

It’s okay to try hard again. Sincerity might be risky, but it’s not foolish. It’s necessary.

The cold, closed hearts formed by the anti-story is breaking apart. In its place is an invitation: to rebuild, to hope, to go all in.

Here’s to being a try-hard again.

After Top Gun: Maverick ended, I cam out of the cinema feeling genuinely elated.

I wasn't 16. I was 38, if I recall correctly. But I refuse to call it immature. Though it was only a film, the total lack of anything cynical made me feel like it was possible, however briefly, to hope without muttering 'meh' to myself and then justifying my lack of engagement.

So, after reading your article, I'm going to make some notes for my next essay and then rewatch Maverick in all of his canyon-flying glory.