Independence Day & the Last Pre-Cynical Generation

Why Gen Z Cracks 9/11 Jokes and Millennials Miss the Old America

Over the long Fourth of July weekend, I found myself indulging on consecutive nights in unplanned cable TV rewatches of a seminal cultural text for a Geriatric Millennial like me:

Independence Day.

Independence Day (1996) features Will Smith punching an alien in the face, Jeff Goldblum uploading a computer virus into an alien mothership, and President Bill Pullman delivering the most patriotic speech of all time: “We will not go quietly into the night!” It's absurd, a bit bombastic, and unrepentantly earnest. Most who attempt to watch it back these days during a commercial-laced airing on channel 879 or the random 24-7 SciFi Roku channel will find it painfully cringe.

But back in 1996, Independence Day was strangely sacred for Millennial tweens. We were in an odd liminal space between the passing of modernism and the coronation of postmodernism in pop culture. Unlike Pulp Fiction or the later Fight Club of 1999, Independence Day was as earnest as any episode of Full House on TGIF. That sort of full-on sincerity was increasingly falling out of fashion as a form of infantile naivety, but it hadn’t been completely buried in the ground next to Journey cassette tapes and the posters of Hulk Hogan carrying an American flag.

Ours was a strange generation stuck between worlds. The Cold War had just ended, and we’d won. History, we were told, had an arc. America was the hero. The future was progress. The story was linear, moral, and upward.

The cartoons of our childhood, like G.I. Joe, preached civic virtue and self-esteem. We remembered what it was like to think Superman was cool. A few televangelists had scandals, but you didn’t hear much about failing pastors in the news. Heck, you really didn’t even know what was going on in the church down the street from you.

It was still a pre-Internet age in 1996. There was a sense of shared coherence—sometimes corny and contradictory, but you hadn’t been programmed to look for all the faults yet. You remembered being proud about your country, your culture, your home, and your church.

That all changed.

9/11 and the Collapse of the Frame

One of the first epiphanies I had about the differences between Millennial and Gen Z cultural inputs came during some of my final years of teaching in the traditional classroom circa 2016 or so. I noticed how teenage male students were suddenly cracking jokes and sharing memes about September 11th–an act that was unfathomable to my Millennial mind. One student even slipped a 9/11 meme into a presentation on Tolkien’s Two Towers in the Lord of the Rings, which hit this Millennial teacher as an act of sacrilege.

To them, Independence Day was completely cringe. To me, it was the very first images my brain recalled on the morning of September 11, 2001, when I watched the World Trade Center buildings collapse on live television. The chaos and destruction of New York City when the aliens attacked with their powerful death ray blast was the closest frame of reference my mind had as I watched the real scenes of people running from the cloud of ash and rubble in New York City on that terrible morning.

If the shock of that horrific terrorist attack wasn’t enough to disrupt my own narrative identity, the scenes on the news that night from the Middle East of people celebrating the attack in the streets by burning American flags completely destroyed my naive Rocky IV view of my country.

I thought we were the good guys?

But Gen Z never lived in that story. September 11 and Independence Day never made sense to them. They had been shaped by a completely different story.

Domicide and the Deconstruction Generation

For Geriatric Millennials, the story we were raised in didn’t just fade—it got torn down inside of us, brick by brick. What happened on 9/11 and the years that followed only strengthened the case that cynical films like Fight Club and Marxist-coded music like Rage Against the Machine “Evil Empire” made. So we learned to question everything: patriotism, religion, institutions, authority, and even the concept of truth itself.

My friend John Vervaeke, who is a leading cognitive scientist studying the “meaning-crisis,” calls this disorienting experience of cultural deconstruction “domicide.”

Domicide is the breakdown or abandonment of the shared symbolic and narrative structures that provide us with a sense of:

Orientation – a meaningful way of navigating the world

Belonging – participation in a story shared with others

Identity – coherence between who I am, where I come from, and where I’m going

We weren’t just doubting a set of beliefs. We were losing a place to belong. Many left the faith traditions in which they were raised. Others abandoned the values and moral structures of their youth. What we didn’t realize was that in walking away from those guiding stories, we often walked away from the communities that held them, leaving us isolated and increasingly discipled by other hurting strangers on the internet.

You could see it in the way irony became a generational coping mechanism, or in the way sincerity got recategorized as cringe. Nothing from that pre-cynical age was sacred anymore and everything became meme-able.

For Millenials, we tended to turn inward and were more inclined to depressed and emo about our domicide. We were the last generation to have lived in an American culture that our great grandparents would have vaguely recognized. Gen Z never had that frame of reference, except through the movies and TV that their older siblings or parents exposed them to, but those were never their native cultural tongue.

Gen Z tended toward a kind of comedic nihilism. Rick and Morty was their Simpsons. Memes, even 9/11 ones, were like the way Millenials and younger Gen X’ers would trade movie or TV show quotes (Milk was a bad choice…Did I do that?…I’ll be back…They may take our lives, but they’ll never take our FREEEEEDOM, etc). Zoomer males made “edits” (video montages, for you old folks like me) of Patrick Bateman in American Psycho and ironically joked about their despair saying, “It’s literally me.”

This might just be a kind of gallows humor that accompanies a generational meaning crisis, and maybe its better than making a whiny emo song, but the more important point here is to take note of how Zoomers process the meaning crisis differntly than Millennials.

Nostalgia for Home

Mixed in with this ironic detachment has been a growing nostalgia for a home that Zoomers never experienced and that Millennials only have faint recollections of. As my colleague, Clay Routledge, has noted, Zoomers are buying vinyl records, rediscovering VHS camcorders, bringing back 90s baggy jeans and cargos, and even post-ironically blasting Creed songs as an attempt at meaning-retrieval.

There are other important signs of this meaning-retrieval process (which I cover in my forthcoming book, tentatively titled Vibe Shift…or Return to Meaning, decision TBD from publisher)…

But what is most important to understand is that this is all a way of responding to domicide. We cannot live without a clear orientation in life, a sense of belonging, and a shared story that forms our narrative identity to pursue the Good. There is something important about reassessing what we’ve lost, reclaiming it, and rebuilding with the knowledge we have now about what did not lead to life.

There’s no going back to that state of innocence–and yes, naivety–that you felt when President Bill Pullman (and yes, I know that’s not the character’s name) gave you his own William Wallace inspired Braveheart speech at the end of Independence Day, but we also need to move beyond our failed project of perpetual deconstruction and cynicism if we are going to find meaning in a shared story again.

That post-cynical wave is here. (Again, more on that to come!)

As I wrote about last week, there are plenty of reasons why cynicism is a failed strategy:

The Lie of the Cynical Genius

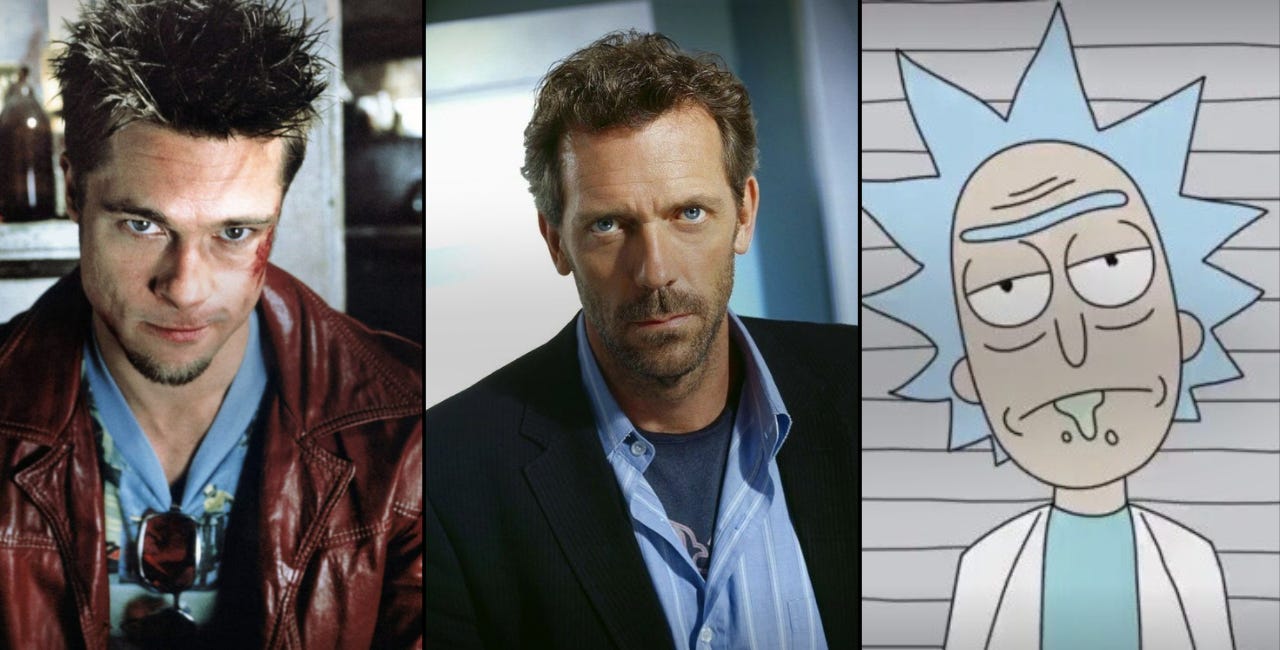

Tyler Durden in Fight Club blew up the credit card companies and gave a generation of disaffected young men a manifesto: nothing is real, nothing matters, and anyone who tells you otherwise is trying to sell you something. Dr. Gregory House from the long-running hit TV show

Paul, I’ve often wondered why nostalgia is such a strong pull. I’ve thought about it a lot. I’m sure each generation experiences it in their own way, but perhaps for us elder millennials (I’m 43), the pull is even stronger than previous groups because the cynical world view has just grown so tiresome. We long to go back to that place of hopefulness we experienced in our youth.

I didn’t perceive that shift toward cultural cynicism as a kid, but it totally makes sense now. I remember when Independence Day movie was a big deal, but yes, the sincerity faded quickly right around the mid 90s. Hopefully you are right and a new shift is underway.